Domitian Denarius

Obverse: CAESAR AVG F DOMITIANVS, laureate head right

Reverse: COS V, She-wolf and twins left, boat below

RSC 51

Domitian Denarius. 76 AD

Obverse: CAESAR AVG F DOMITIANVS, laureate head right

Reverse: COS IIII, winged Pegasus standing right with

raising left foreleg

BMC 193, RSC 47

Domitian. AR denarius. AD 87

Obverse: IMP CAES DOMIT AVG GERM PM TR P VII, laureate

head left.

Reverse: IMP XIIII COS XIII CENS P PP, Minerva standing

left, holding spear.

RIC 521; RSC 222; BMC 114

|

|

Domitian (Latin: Titus Flavius Caesar Domitianus Augustus; 24 October 51

– 18 September 96) was the Emperor of Rome from 81 to 96. He was

the younger brother of Titus and son of Vespasian, his two predecessors

on the throne, and the last member of the Flavian dynasty. During

his reign, his authoritarian rule put him at sharp odds with the senate,

whose powers he drastically curtailed.

After the death of his brother, Domitian was declared emperor by the Praetorian

Guard. His 15-year reign was the longest since that of Tiberius.

As emperor, Domitian strengthened the economy by revaluing the Roman coinage,

expanded the border defenses of the empire, and initiated a massive building

program to restore the damaged city of Rome. Significant wars were

fought in Britain, where his general Agricola attempted to conquer Caledonia

(Scotland), and in Dacia, where Domitian was unable to procure a decisive

victory against king Decebalus. Domitian's government exhibited totalitarian

characteristics; he saw himself as the new Augustus, an enlightened despot

destined to guide the Roman Empire into a new era of brilliance.

Religious, military, and cultural propaganda fostered a cult of personality,

and by nominating himself perpetual censor, he sought to control public

and private morals. As a consequence, Domitian was popular with the

people and army, but considered a tyrant by members of the Roman Senate.

Domitian's reign came to an end in 96 when he was assassinated by court

officials. He was succeeded the same day by his advisor Nerva.

After his death, Domitian's memory was condemned to oblivion by the Roman

Senate, while senatorial authors such as Tacitus, Pliny the Younger, and

Suetonius propagated the view of Domitian as a cruel and paranoid tyrant.

Modern revisionists instead, have characterized Domitian as a ruthless,

but efficient autocrat whose cultural, economic and political program provided

the foundation of the peaceful second century.

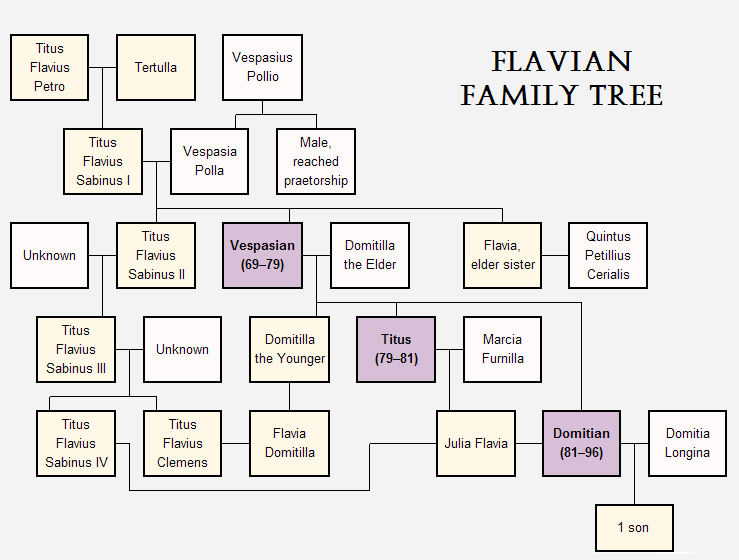

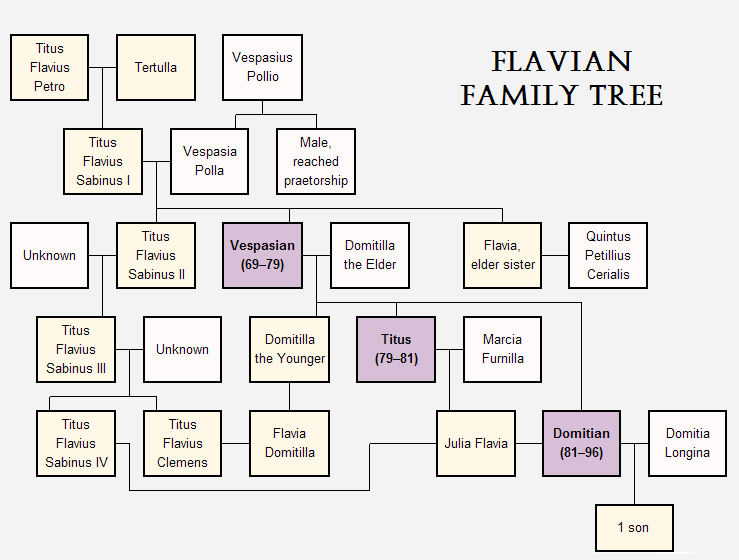

Family and background:

The Flavian family tree, indicating the descendants

of Titus Flavius Petro and Tertulla.

Domitian was born in Rome on 24 October 51, the youngest son of Titus Flavius

Vespasianus — commonly known as Vespasian — and Flavia Domitilla Major.

He had an older sister, Domitilla the Younger, and brother, also named

Titus Flavius Vespasianus.

Decades of civil war during the 1st century BC had contributed greatly

to the demise of the old aristocracy of Rome, which a new Italian nobility

gradually replaced in prominence during the early part of the 1st century.

One such family, the Flavians, or gens Flavia, rose from relative obscurity

to prominence in just four generations, acquiring wealth and status under

the emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Domitian's great-grandfather,

Titus Flavius Petro, had served as a centurion under Pompey during Caesar's

civil war. His military career ended in disgrace when he fled the

battlefield at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC.

Nevertheless, Petro managed to improve his status by marrying the extremely

wealthy Tertulla, whose fortune guaranteed the upwards mobility of Petro's

son Titus Flavius Sabinus I, Domitian's grandfather. Sabinus himself

amassed further wealth and possible equestrian status through his services

as tax collector in Asia and banker in Helvetia (modern Switzerland).

By marrying Vespasia Polla he allied the Flavian family to the more prestigious

gens Vespasia, ensuring the elevation of his sons Titus Flavius Sabinus

II and Vespasian to senatorial rank.

The political career of Vespasian included the offices of quaestor, aedile,

and praetor, and culminated with a consulship in 51, the year of Domitian's

birth. As a military commander, Vespasian gained early renown by

participating in the Roman invasion of Britain in 43. Nevertheless,

ancient sources allege poverty for the Flavian family at the time of Domitian's

upbringing, even claiming Vespasian had fallen into disrepute under the

emperors Caligula (37–41) and Nero (54–68). Modern history has refuted

these claims, suggesting these stories later circulated under Flavian rule

as part of a propaganda campaign to diminish success under the less reputable

Emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and to maximize achievements under

Emperor Claudius (41–54) and his son Britannicus.

By all appearances, the Flavians enjoyed high imperial favour throughout

the 40s and 60s. While Titus received a court education in the company

of Britannicus, Vespasian pursued a successful political and military career.

Following a prolonged period of retirement during the 50s, he returned

to public office under Nero, serving as proconsul of the Africa province

in 63, and accompanying the emperor during an official tour of Greece in

66.

The same year the Jews of the Judaea province revolted against the Roman

Empire in what is now known as the First Jewish-Roman War. Vespasian

was assigned to lead the Roman army against the insurgents, with Titus

— who had completed his military education by this time — in charge of

a legion.

Youth and character:

Of the three Flavian emperors, Domitian would rule the longest, despite

the fact that his youth and early career were largely spent in the shadow

of his older brother. Titus had gained military renown during the

First Jewish–Roman War. After their father Vespasian became emperor

in 69 following the civil war known as the Year of the Four Emperors, Titus

held a great many offices, while, Domitian received honours, but no responsibilities.

By the time he was 6 years old, Domitian's mother and sister had long since

died, while his father and brother were continuously active in the Roman

military, commanding armies in Germania and Judaea. For Domitian,

this meant that a significant part of his adolescence was spent in the

absence of his near relatives. During the Jewish-Roman wars, he was

likely taken under the care of his uncle Titus Flavius Sabinus II, at the

time serving as city prefect of Rome; or possibly even Marcus Cocceius

Nerva, a loyal friend of the Flavians and the future successor to Domitian.

He received the education of a young man of the privileged senatorial class,

studying rhetoric and literature. In his biography in the Lives of

the Twelve Caesars, Suetonius attests to Domitian's ability to quote the

important poets and writers such as Homer or Virgil on appropriate occasions,

and describes him as a learned and educated adolescent, with elegant conversation.

Among his first published works were poetry, as well as writings on law

and administration.

Unlike his brother Titus, Domitian was not educated at court. Whether

he received formal military training is not recorded, but according to

Suetonius, he displayed considerable marksmanship with the bow and arrow.

A detailed description of Domitian's appearance and character is provided

by Suetonius, who devotes a substantial part of his biography to his personality:

"He was tall of stature, with a modest expression and a high colour. His

eyes were large, but his sight was somewhat dim. He was handsome and graceful

too, especially when a young man, and indeed in his whole body with the

exception of his feet, the toes of which were somewhat cramped. In later

life he had the further disfigurement of baldness, a protruding belly,

and spindling legs, though the latter had become thin from a long illness."

Domitian was allegedly extremely sensitive regarding his baldness, which

he disguised in later life by wearing wigs. According to Suetonius,

he even wrote a book on the subject of hair care. With regard to

Domitian's personality, however, the account of Suetonius alternates sharply

between portraying Domitian as the emperor-tyrant, a man both physically

and intellectually lazy, and the intelligent, refined personality drawn

elsewhere.

Historian Brian Jones concludes in The Emperor Domitian that assessing

the true nature of Domitian's personality is inherently complicated by

the bias of the surviving sources. Common threads nonetheless emerge

from the available evidence. He appears to have lacked the natural

charisma of his brother and father. He was prone to suspicion, displayed

an odd, sometimes self-deprecating sense of humour, and often communicated

in cryptic ways.

This ambiguity of character was further exacerbated by his remoteness,

and as he grew older, he increasingly displayed a preference for solitude,

which may have stemmed from his isolated upbringing. Indeed, by the

age of eighteen nearly all of his closest relatives had died by war or

disease. Having spent the greater part of his early life in the twilight

of Nero's reign, his formative years would have been strongly influenced

by the political turmoil of the 60s, culminating with the civil war of

69, which brought his family to power.

Rise of the Flavian dynasty:

On 9 June 68, amid growing opposition of the Senate and the army, Nero

committed suicide and with him the Julio-Claudian dynasty came to an end.

Chaos ensued, leading to a year of brutal civil war known as the Year of

the Four Emperors, during which the four most influential generals in the

Roman Empire—Galba, Otho, Vitellius and Vespasian—successively vied for

imperial power.

News of Nero's death reached Vespasian as he was preparing to besiege the

city of Jerusalem. Almost simultaneously the Senate had declared

Galba, then governor of Hispania Tarraconensis (modern northern Spain),

as Emperor of Rome. Rather than continue his campaign, Vespasian

decided to await further orders and send Titus to greet the new Emperor.

Before reaching Italy, Titus learnt that Galba had been murdered and replaced

by Otho, the governor of Lusitania (modern Portugal). At the same

time Vitellius and his armies in Germania had risen in revolt and prepared

to march on Rome, intent on overthrowing Otho. Not wanting to risk

being taken hostage by one side or the other, Titus abandoned the journey

to Rome and rejoined his father in Judaea.

Otho and Vitellius realized the potential threat posed by the Flavian faction.

With four legions at his disposal, Vespasian commanded a strength of nearly

80,000 soldiers. His position in Judaea further granted him the advantage

of being nearest to the vital province of Egypt, which controlled the grain

supply to Rome. His brother Titus Flavius Sabinus II, as city prefect,

commanded the entire city garrison of Rome. Tensions among the Flavian

troops ran high but so long as either Galba or Otho remained in power,

Vespasian refused to take action.

When Otho was defeated by Vitellius at the First Battle of Bedriacum, the

armies in Judaea and Egypt took matters into their own hands and declared

Vespasian emperor on 1 July 69. Vespasian accepted and entered an

alliance with Gaius Licinius Mucianus, the governor of Syria, against Vitellius.

A strong force drawn from the Judaean and Syrian legions marched on Rome

under the command of Mucianus, while Vespasian travelled to Alexandria,

leaving Titus in charge of ending the Jewish rebellion.

In Rome, Domitian was placed under house arrest by Vitellius, as a safeguard

against Flavian aggression. Support for the old emperor waned as

more legions around the empire pledged their allegiance to Vespasian.

On 24 October 69, the forces of Vitellius and Vespasian met at the Second

Battle of Bedriacum, which ended in a crushing defeat for the armies of

Vitellius.

In despair, Vitellius attempted to negotiate a surrender. Terms of peace,

including a voluntary abdication, were agreed upon with Titus Flavius Sabinus

II but the soldiers of the Praetorian Guard—the imperial bodyguard—considered

such a resignation disgraceful and prevented Vitellius from carrying out

the treaty. On the morning of 18 December, the emperor appeared to

deposit the imperial insignia at the Temple of Concord but at the last

minute retraced his steps to the Imperial palace. In the confusion,

the leading men of the state gathered at Sabinus' house, proclaiming Vespasian

as Emperor, but the multitude dispersed when Vitellian cohorts clashed

with the armed escort of Sabinus, who was forced to retreat to the Capitoline

Hill.

During the night, he was joined by his relatives, including Domitian.

The armies of Mucianus were nearing Rome but the besieged Flavian party

did not hold out for longer than a day. On 19 December, Vitellianists

burst onto the Capitol and in a skirmish, Sabinus was captured and executed.

Domitian managed to escape by disguising himself as a worshipper of Isis

and spent the night in safety with one of his father's supporters, Cornelius

Primus.

By the afternoon of 20 December, Vitellius was dead, his armies having

been defeated by the Flavian legions. With nothing more to be feared,

Domitian came forward to meet the invading forces; he was universally saluted

by the title of Caesar and the mass of troops conducted him to his father's

house. The following day, 21 December, the Senate proclaimed Vespasian

emperor of the Roman Empire.

Aftermath of the war:

Although the war had officially ended, a state of anarchy and lawlessness

pervaded in the first days following the demise of Vitellius. Order

was properly restored by Mucianus in early 70 but Vespasian did not enter

Rome until September of that year. In the meantime, Domitian acted

as the representative of the Flavian family in the Roman Senate.

He received the title of Caesar and was appointed praetor with consular

power.

The ancient historian Tacitus describes Domitian's first speech in the

Senate as brief and measured, at the same time noting his ability to elude

awkward questions. Domitian's authority was merely nominal, however,

foreshadowing what was to be his role for at least ten more years.

By all accounts, Mucianus held the real power in Vespasian's absence and

he was careful to ensure that Domitian, still only eighteen years old,

did not overstep the boundaries of his function. Strict control was

also maintained over the young Caesar's entourage, promoting away Flavian

generals such as Arrius Varus and Antonius Primus and replacing them by

more reliable men such as Arrecinus Clemens.

Equally curtailed by Mucianus were Domitian's military ambitions. The civil

war of 69 had severely destabilized the provinces, leading to several local

uprisings such as the Batavian revolt in Gaul. Batavian auxiliaries

of the Rhine legions, led by Gaius Julius Civilis, had rebelled with the

aid of a faction of Treveri under the command of Julius Classicus.

Seven legions were sent from Rome, led by Vespasian's brother-in-law Quintus

Petillius Cerialis.

Although the revolt was quickly suppressed, exaggerated reports of disaster

prompted Mucianus to depart the capital with reinforcements of his own.

Domitian eagerly sought the opportunity to attain military glory and joined

the other officers with the intention of commanding a legion of his own.

According to Tacitus, Mucianus was not keen on this prospect but since

he considered Domitian a liability in any capacity that was entrusted to

him, he preferred to keep him close at hand rather than in Rome.

When news arrived of Cerialis' victory over Civilis, Mucianus tactfully

dissuaded Domitian from pursuing further military endeavours. Domitian

then wrote to Cerialis personally, suggesting he hand over command of his

army but, once again, he was snubbed. With the return of Vespasian

in late September, his political role was rendered all but obsolete and

Domitian withdrew from government devoting his time to arts and literature.

Marriage:

Where his political and military career had ended in disappointment, Domitian's

private affairs were more successful. In 70 Vespasian attempted to

arrange a dynastic marriage between his youngest son and the daughter of

Titus, Julia Flavia, but Domitian was adamant in his love for Domitia Longina,

going so far as to persuade her husband, Lucius Aelius Lamia, to divorce

her so that Domitian could marry her himself. Despite its initial

recklessness, the alliance was very prestigious for both families.

Domitia Longina was the younger daughter of Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo, a

respected general and honoured politician who had distinguished himself

for his leadership in Armenia. Following the failed Pisonian conspiracy

against Nero in 65, he had been forced to commit suicide. The new

marriage not only re-established ties to senatorial opposition, but also

served the broader Flavian propaganda of the time, which sought to diminish

Vespasian's political success under Nero. Instead connections to

Claudius and Britannicus were emphasised, and Nero's victims, or those

otherwise disadvantaged by him, rehabilitated.

In 80, Domitia and Domitian's only attested son was born. It is not known

what the boy's name was, but he died in childhood in 83. Shortly

following his accession as Emperor, Domitian bestowed the honorific title

of Augusta upon Domitia, while their son was deified, appearing as such

on the reverse of coin types from this period. Nevertheless, the

marriage appears to have faced a significant crisis in 83. For reasons

unknown, Domitian briefly exiled Domitia, and then soon recalled her, either

out of love or due to rumours that he was carrying on a relationship with

his niece Julia Flavia. Jones argues that most likely he did so for

her failure to produce an heir. By 84, Domitia had returned to the

palace, where she lived for the remainder of Domitian's reign without incident.

Little is known of Domitia's activities as Empress, or how much influence

she wielded in Domitian's government, but it seems her role was limited.

From Suetonius, we know that she at least accompanied the Emperor to the

amphitheatre, while the Jewish writer Josephus speaks of benefits he received

from her. It is not known whether Domitian had other children, but

he did not marry again. Despite allegations by Roman sources of adultery

and divorce, the marriage appears to have been happy.

Ceremonial heir (71–81):

Prior to becoming Emperor, Domitian's role in the Flavian government was

largely ceremonial. In June 71, Titus returned triumphant from the

war in Judaea. Ultimately, the rebellion had claimed the lives of

over 1 million people, a majority of whom were Jewish. The city and

temple of Jerusalem were completely destroyed, its most valuable treasures

carried off by the Roman army, and nearly 100,000 people were captured

and enslaved.

For his victory, the Senate awarded Titus a Roman triumph. On the

day of the festivities, the Flavian family rode into the capital, preceded

by a lavish parade that displayed the spoils of the war. The family

procession was headed by Vespasian and Titus, while Domitian, riding a

magnificent white horse, followed with the remaining Flavian relatives.

Leaders of the Jewish resistance were executed in the Forum Romanum, after

which the procession closed with religious sacrifices at the Temple of

Jupiter. A triumphal arch, the Arch of Titus, was erected at the

south-east entrance to the Forum to commemorate the successful end of the

war.

Yet the return of Titus further highlighted the comparative insignificance

of Domitian, both militarily and politically. As the eldest and most

experienced of Vespasian's sons, Titus shared tribunician power with his

father, received seven consulships, the censorship, and was given command

of the Praetorian Guard; powers that left no doubt he was the designated

heir to the Empire. As a second son, Domitian held honorary titles,

such as Caesar or Princeps Iuventutis, and several priesthoods, including

those of augur, pontifex, frater arvalis, magister frater arvalium, and

sacerdos collegiorum omnium, but no office with imperium.

He held six consulships during Vespasian's reign but only one of these,

in 73, was an ordinary consulship. The other five were less prestigious

suffect consulships, which he held in 71, 75, 76, 77 and 79 respectively,

usually replacing his father or brother in mid-January. While ceremonial,

these offices no doubt gained Domitian valuable experience in the Roman

Senate, and may have contributed to his later reservations about its relevance.

Under Vespasian and Titus, non-Flavians were virtually excluded from the

important public offices. Mucianus himself all but disappeared from

historical records during this time, and it is believed he died sometime

between 75 and 77. Real power was unmistakably concentrated in the

hands of the Flavian faction; the weakened Senate only maintained the facade

of democracy.

Because Titus effectively acted as co-emperor with his father, no abrupt

change in Flavian policy occurred when Vespasian died on 23 June 79.

Titus assured Domitian that full partnership in the government would soon

be his, but neither tribunician power nor imperium of any kind was conferred

upon him during Titus' brief reign. The new Emperor was not eager

to alter this arrangement: he was under forty and at the height of his

power.

Two major disasters struck during 79 and 80. On 24 August 79, Mount

Vesuvius erupted, burying the surrounding cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum

under metres of ash and lava; the following year, a fire broke out in Rome

that lasted three days and that destroyed a number of important public

buildings. Consequently, Titus spent much of his reign coordinating

relief efforts and restoring damaged property. On 13 September 81

after barely two years in office, he unexpectedly died of fever during

a trip to the Sabine territories.

Ancient authors have implicated Domitian in the death of his brother, either

by directly accusing him of murder, or implying he left the ailing Titus

for dead, even alleging that during his lifetime, Domitian was openly plotting

against his brother. It is difficult to assess the factual veracity

of these statements given the known bias of the surviving sources.

Brotherly affection was likely at a minimum, but this was hardly surprising,

considering that Domitian had barely seen Titus after the age of seven.

Whatever the nature of their relationship, Domitian seems to have displayed

little sympathy when his brother lay dying, instead making for the Praetorian

camp where he was proclaimed emperor. The following day, 14 September,

the Senate confirmed Domitian's powers, granting tribunician power, the

office of Pontifex Maximus, and the titles of Augustus, and Pater Patriae.

Emperor (81–96)

Rule:

As Emperor, Domitian quickly dispensed with the republican facade his father

and brother had maintained during their reign. By moving the centre

of government (more or less formally) to the imperial court, Domitian openly

rendered the Senate's powers obsolete. In his view, the Roman Empire

was to be governed as a divine monarchy with himself as the benevolent

despot at its head.

In addition to exercising absolute political power, Domitian believed the

emperor's role encompassed every aspect of daily life, guiding the Roman

people as a cultural and moral authority. To usher in the new era,

he embarked on ambitious economic, military and cultural programs with

the intention of restoring the Empire to the splendour it had seen under

the Emperor Augustus.

Despite these grand designs Domitian was determined to govern the Empire

conscientiously and scrupulously. He became personally involved in

all branches of the administration: edicts were issued governing the smallest

details of everyday life and law, while taxation and public morals were

rigidly enforced. According to Suetonius, the imperial bureaucracy

never ran more efficiently than under Domitian, whose exacting standards

and suspicious nature maintained historically low corruption among provincial

governors and elected officials.

Although he made no pretence regarding the significance of the Senate under

his absolute rule, those senators he deemed unworthy were expelled from

the Senate, and in the distribution of public offices he rarely favoured

family members; a policy that stood in contrast to the nepotism practiced

by Vespasian and Titus. Above all, however, Domitian valued loyalty

and malleability in those he assigned to strategic posts, qualities he

found more often in men of the equestrian order than in members of the

Senate or his own family, whom he regarded with suspicion, and promptly

removed from office if they disagreed with imperial policy.

The reality of Domitian's autocracy was further highlighted by the fact

that, more than any emperor since Tiberius, he spent significant periods

of time away from the capital. Although the Senate's power had been

in decline since the fall of the Republic, under Domitian the seat of power

was no longer even in Rome, but rather wherever the Emperor was.

Until the completion of the Flavian Palace on the Palatine Hill, the imperial

court was situated at Alba or Circeii, and sometimes even farther afield.

Domitian toured the European provinces extensively, and spent at least

three years of his reign in Germania and Illyricum, conducting military

campaigns on the frontiers of the Empire.

Economy:

Upon his accession, Domitian revalued the Roman currency by increasing

the silver content of the denarius by 12%. This coin commemorates

the deification of Domitian's son.

Domitian's tendency towards micromanagement was nowhere more evident than

in his financial policy. The question of whether Domitian left the

Roman Empire in debt or with a surplus at the time of his death has been

fiercely debated. The evidence points to a balanced economy for the

greater part of Domitian's reign. Upon his accession he revalued

the Roman currency dramatically. He increased the silver purity of

the denarius from 90% to 98% — the actual silver weight increasing from

2.87 grams to 3.26 grams. A financial crisis in 85 forced a devaluation

of the silver purity and weight to 93.5% and 3.04 grams respectively.

Nevertheless, the new values were still higher than the levels that Vespasian

and Titus had maintained during their reigns. Domitian's rigorous

taxation policy ensured that this standard was sustained for the following

eleven years. Coinage from this era displays a highly consistent

degree of quality including meticulous attention to Domitian's titulature

and refined artwork on the reverse portraits.

Jones estimates Domitian's annual income at more than 1.2 billion sestertii,

of which over one-third would presumably have been spent maintaining the

Roman army. The other major expense was the extensive reconstruction

of Rome. At the time of Domitian's accession the city was still suffering

from the damage caused by the Great Fire of 64, the civil war of 69 and

the fire in 79.

Much more than a renovation project, Domitian's building program was intended

to be the crowning achievement of an Empire-wide cultural renaissance.

Around fifty structures were erected, restored or completed, achievements

second only to those of Augustus. Among the most important new structures

were an odeon, a stadium, and an expansive palace on the Palatine Hill

known as the Flavian Palace, which was designed by Domitian's master architect

Rabirius.

The most important building Domitian restored was the Temple of Jupiter

on the Capitoline Hill, said to have been covered with a gilded roof.

Among those completed were the Temple of Vespasian and Titus, the Arch

of Titus and the Colosseum, to which he added a fourth level and finished

the interior seating area.

In order to appease the people of Rome an estimated 135 million sestertii

was spent on donatives, or congiaria, throughout Domitian's reign.

The Emperor also revived the practice of public banquets, which had been

reduced to a simple distribution of food under Nero, while he invested

large sums on entertainment and games. In 86 he founded the Capitoline

Games, a quadrennial contest comprising athletic displays, chariot racing,

and competitions for oratory, music and acting.

Domitian himself supported the travel of competitors from all corners of

the Empire to Rome and distributed the prizes. Innovations were also

introduced into the regular gladiatorial games such as naval contests,

nighttime battles, and female and dwarf gladiator fights. Lastly, he added

two new factions to the chariot races, Gold and Purple, to race against

the existing White, Red, Green and Blue factions.

Military campaigns:

The military campaigns undertaken during Domitian's reign were generally

defensive in nature, as the Emperor rejected the idea of expansionist warfare.

His most significant military contribution was the development of the Limes

Germanicus, which encompassed a vast network of roads, forts and watchtowers

constructed along the Rhine river to defend the Empire. Nevertheless,

several important wars were fought in Gaul, against the Chatti, and across

the Danube frontier against the Suebi, the Sarmatians, and the Dacians.

The conquest of Britain continued under the command of Gnaeus Julius Agricola,

who expanded the Roman Empire as far as Caledonia, or modern day Scotland.

Domitian also founded a new legion in 82, the Legio I Minervia, to fight

against the Chatti. Domitian is also credited on the easternmost

evidence of Roman presence, the rock inscription near Boyukdash mountain,

in present-day Azerbaijan. As judged by the carved titles of Caesar,

Augustus and Germanicus, the related march took place between 84 and 96

AD.

Domitian's administration of the Roman army was characterized by the same

fastidious involvement he exhibited in other branches of the government.

His competence as a military strategist was criticized by his contemporaries

however. Although he claimed several triumphs, these were largely

propaganda manoeuvres. Tacitus derided Domitian's victory against

the Chatti as a "mock triumph", and criticized his decision to retreat

in Britain following the conquests of Agricola.

Nevertheless, Domitian appears to have been very popular among the soldiers,

spending an estimated three years of his reign among the army on campaigns—more

than any emperor since Augustus—and raising their pay by one-third.

While the army command may have disapproved of his tactical and strategic

decisions, the loyalty of the common soldier was unquestioned.

Campaign against the Chatti:

Once Emperor, Domitian immediately sought to attain his long delayed military

glory. As early as 82, or possibly 83, he went to Gaul, ostensibly

to conduct a census, and suddenly ordered an attack on the Chatti.

For this purpose, a new legion was founded, Legio I Minervia, which constructed

some 75 kilometres (46 mi) of roads through Chattan territory to uncover

the enemy's hiding places.

Although little information survives of the battles fought, enough early

victories were apparently achieved for Domitian to be back in Rome by the

end of 83, where he celebrated an elaborate triumph and conferred upon

himself the title of Germanicus. Domitian's supposed victory was

much scorned by ancient authors, who described the campaign as "uncalled

for", and a "mock triumph". The evidence lends some credence to these

claims, as the Chatti would later play a significant role during the revolt

of Saturninus in 89.

Conquest of Britain (77–84):

One of the most detailed reports of military activity under the Flavian

dynasty was written by Tacitus, whose biography of his father-in-law Gnaeus

Julius Agricola largely concerns the conquest of Britain between 77 and

84. Agricola arrived c. 77 as governor of Roman Britain, immediately

launching campaigns into Caledonia (modern Scotland).

In 82 Agricola crossed an unidentified body of water and defeated peoples

unknown to the Romans until then. He fortified the coast facing Ireland,

and Tacitus recalls that his father-in-law often claimed the island could

be conquered with a single legion and a few auxiliaries. He had given

refuge to an exiled Irish king whom he hoped he might use as the excuse

for conquest. This conquest never happened, but some historians believe

that the crossing referred to was in fact a small-scale exploratory or

punitive expedition to Ireland.

Turning his attention from Ireland, the following year Agricola raised

a fleet and pushed beyond the Forth into Caledonia. To aid the advance,

a large legionary fortress was constructed at Inchtuthil. In the

summer of 84, Agricola faced the armies of the Caledonians, led by Calgacus,

at the Battle of Mons Graupius. Although the Romans inflicted heavy

losses on the enemy, two-thirds of the Caledonian army escaped and hid

in the Scottish marshes and Highlands, ultimately preventing Agricola from

bringing the entire British island under his control.

In 85, Agricola was recalled to Rome by Domitian, having served for more

than six years as governor, longer than normal for consular legates during

the Flavian era. Tacitus claims that Domitian ordered his recall

because Agricola's successes outshone the Emperor's own modest victories

in Germania. The relationship between Agricola and the Emperor is

unclear: on the one hand, Agricola was awarded triumphal decorations and

a statue, on the other, Agricola never again held a civil or military post

in spite of his experience and renown. He was offered the governorship

of the province of Africa but declined it, either due to ill health or,

as Tacitus claims, the machinations of Domitian.

Not long after Agricola's recall from Britain, the Roman Empire entered

into war with the Kingdom of Dacia in the East. Reinforcements were

needed, and in 87 or 88, Domitian ordered a large-scale strategic withdrawal

of troops in the British province. The fortress at Inchtuthil was

dismantled and the Caledonian forts and watchtowers abandoned, moving the

Roman frontier some 120 kilometres (75 mi) further south. The army

command may have resented Domitian's decision to retreat, but to him the

Caledonian territories never represented anything more than a loss to the

Roman treasury.

Dacian wars (85–88):

The most significant threat the Roman Empire faced during the reign of

Domitian arose from the northern provinces of Illyricum, where the Suebi,

the Sarmatians and the Dacians continuously harassed Roman settlements

along the Danube river. Of these, the Sarmatians and the Dacians

posed the most formidable threat. In approximately 84 or 85 the Dacians,

led by King Decebalus, crossed the Danube into the province of Moesia,

wreaking havoc and killing the Moesian governor Oppius Sabinus.

Domitian quickly launched a counteroffensive, personally travelling to

the region accompanied by a large force commanded by his praetorian prefect

Cornelius Fuscus. Fuscus successfully drove the Dacians back across

the border in mid-85, prompting Domitian to return to Rome and celebrate

his second triumph.

The victory proved short-lived, however: as early in 86 Fuscus embarked

on an ill-fated expedition into Dacia, which resulted in the complete destruction

of the fifth legion, Legio V Alaudae, in the First Battle of Tapae. Fuscus

was killed, and the battle standard of the Praetorian Guard was lost.

The loss of the battle standard, or aquila, was indicative of a crushing

defeat and a serious affront to Roman national pride.

Domitian returned to Moesia in August 86. He divided the province into

Lower Moesia and Upper Moesia, and transferred three additional legions

to the Danube. In 87, the Romans invaded Dacia once more, this time

under the command of Tettius Julianus, and finally defeated Decebalus in

late 88 at the same site where Fuscus had previously perished. An

attack on the Dacian capital Sarmizegetusa was forestalled when new troubles

arose on the German frontier in 89.

In order to avert having to conduct a war on two fronts, Domitian agreed

to terms of peace with Decebalus, negotiating free access of Roman troops

through the Dacian region while granting Decebalus an annual subsidy of

8 million sesterces. Contemporary authors severely criticized this

treaty, which was considered shameful to the Romans and left the deaths

of Sabinus and Fuscus unavenged. For the remainder of Domitian's

reign Dacia remained a relatively peaceful client kingdom, but Decebalus

used the Roman money to fortify his defenses.

Domitian probably wanted a new war against the Dacians, and reinforced

Upper Moesia with two more cavalry units brought from Syria and with at

least five cohorts brought from Pannonia. Trajan continued Domitian's

policy and added two more units to the auxiliary forces of Upper Moesia,

and then he used the build up of troops for his Dacian wars. Eventually

the Romans achieved a decisive victory against Decebalus in 106.

Again, the Roman army sustained heavy losses, but Trajan succeeded in capturing

Sarmizegetusa and, importantly, annexed the Dacian gold and silver mines.

Religious policy:

Domitian firmly believed in the traditional Roman religion, and personally

saw to it that ancient customs and morals were observed throughout his

reign. In order to justify the divine nature of the Flavian rule,

Domitian emphasized connections with the chief deity Jupiter, perhaps most

significantly through the impressive restoration of the Temple of Jupiter

on the Capitoline Hill. A small chapel dedicated to Jupiter Conservator

was also constructed near the house where Domitian had fled to safety on

20 December 69. Later in his reign, he replaced it with a more expansive

building, dedicated to Jupiter Custos.

The goddess he worshipped the most zealously, however, was Minerva.

Not only did he keep a personal shrine dedicated to her in his bedroom,

she regularly appeared on his coinage—in four different attested reverse

types—and he founded a legion, Legio I Minervia, in her name.

Domitian also revived the practice of the imperial cult, which had fallen

somewhat out of use under Vespasian. Significantly, his first act

as an Emperor was the deification of his brother Titus. Upon their

deaths, his infant son, and niece, Julia Flavia, were likewise enrolled

among the gods. With regards to the emperor himself as a religious

figure, both Suetonius and Cassius Dio allege that Domitian officially

gave himself the title of Dominus et Deus. However, not only did

he reject the title of Dominus during his reign, but since he issued no

official documentation or coinage to this effect, historians such as Brian

Jones contend that such phrases were addressed to Domitian by flatterers

who wished to earn favors from the emperor.

To foster the worship of the imperial family, he erected a dynastic mausoleum

on the site of Vespasian's former house on the Quirinal, and completed

the Temple of Vespasian and Titus, a shrine dedicated to the worship of

his deified father and brother. To memorialize the military triumphs

of the Flavian family, he ordered the construction of the Templum Divorum

and the Templum Fortuna Redux, and completed the Arch of Titus.

Construction projects such as these constituted only the most visible part

of Domitian's religious policy, which also concerned itself with the fulfilment

of religious law and public morals. In 85, he nominated himself perpetual

censor, the office that held the task of supervising Roman morals and conduct.

Once again, Domitian acquitted himself of this task dutifully, and with

care. He renewed the Lex Iulia de Adulteriis Coercendis, under which

adultery was punishable by exile. From the list of jurors he struck

an equestrian who had divorced his wife and taken her back, while an ex-quaestor

was expelled from the Senate for acting and dancing.

Domitian also heavily prosecuted corruption among public officials, removing

jurors if they accepted bribes and rescinding legislation when a conflict

of interest was suspected. He ensured that libellous writings, especially

those directed against himself, were punishable by exile or death.

Actors were likewise regarded with suspicion, as their performances provided

an opportunity for satire at the expense of the government. Consequently,

he forbade mimes from appearing on stage in public.

In 87, Vestal Virgins were found to have broken their sacred vows of lifelong

public chastity. As the Vestals were regarded as daughters of the community,

this offense essentially constituted incest. Accordingly, those found

guilty of any such transgression were condemned to death, either by a manner

of their choosing, or according to the ancient fashion, which dictated

that Vestals should be buried alive.

Foreign religions were tolerated insofar as they did not interfere with

public order, or could be assimilated with the traditional Roman religion.

The worship of Egyptian deities in particular flourished under the Flavian

dynasty, to an extent not seen again until the reign of Commodus.

Veneration of Serapis and Isis, who were identified with Jupiter and Minerva

respectively, was especially prominent.

4th century writings by Eusebius of Caesarea maintain that Jews and Christians

were heavily persecuted toward the end of Domitian's reign. The Book

of Revelation is thought by some to have been written during this period.

Although Jews were heavily taxed, no contemporary authors mention trials

or executions based on religious offenses other than those within the Roman

religion.

Opposition

Revolt of Governor Saturninus (89):

On 1 January 89, the governor of Germania Superior, Lucius Antonius Saturninus,

and his two legions at Mainz, Legio XIV Gemina and Legio XXI Rapax, revolted

against the Roman Empire with the aid of the Germanic Chatti people.

The precise cause for the rebellion is uncertain, although it appears to

have been planned well in advance. The Senatorial officers may have

disapproved of Domitian's military strategies, such as his decision to

fortify the German frontier rather than attack, as well as his recent retreat

from Britain, and finally the disgraceful policy of appeasement towards

Decebalus.

At any rate, the uprising was strictly confined to Saturninus' province,

and quickly detected once the rumour spread across the neighbouring provinces.

The governor of Germania Inferior, Aulus Bucius Lappius Maximus, moved

to the region at once, assisted by the procurator of Rhaetia, Titus Flavius

Norbanus. From Spain, Trajan was summoned, while Domitian himself

came from Rome with the Praetorian Guard.

By a stroke of luck, a thaw prevented the Chatti from crossing the Rhine

and coming to Saturninus' aid. Within twenty-four days the rebellion

was crushed, and its leaders at Mainz savagely punished. The mutinous

legions were sent to the front in Illyricum, while those who had assisted

in their defeat were duly rewarded.

Lappius Maximus received the governorship of the province of Syria, a second

consulship in May 95, and finally a priesthood, which he still held in

102. Titus Flavius Norbanus may have been appointed to the prefecture

of Egypt, but almost certainly became prefect of the Praetorian Guard by

94, with Titus Petronius Secundus as his colleague. Domitian opened

the year following the revolt by sharing the consulship with Marcus Cocceius

Nerva, suggesting the latter had played a part in uncovering the conspiracy,

perhaps in a fashion similar to the one he played during the Pisonian conspiracy

under Nero.

Although little is known about the life and career of Nerva before his

accession as Emperor in 96, he appears to have been a highly adaptable

diplomat, surviving multiple regime changes and emerging as one of the

Flavians' most trusted advisors. His consulship may therefore have

been intended to emphasize the stability and status quo of the regime.

The revolt had been suppressed and the Empire returned to order.

Relationship with the Senate:

Since the fall of the Republic, the authority of the Roman Senate had largely

eroded under the quasi-monarchical system of government established by

Augustus, known as the Principate. The Principate allowed the existence

of a de facto dictatorial regime, while maintaining the formal framework

of the Roman Republic. Most Emperors upheld the public facade of

democracy, and in return the Senate implicitly acknowledged the Emperor's

status as a de facto monarch.

Some rulers handled this arrangement with less subtlety than others.

Domitian was not so subtle. From the outset of his reign, he stressed

the reality of his autocracy. He disliked aristocrats and had no

fear of showing it, withdrawing every decision-making power from the Senate,

and instead relying on a small set of friends and equestrians to control

the important offices of state.

The dislike was mutual. After Domitian's assassination, the senators of

Rome rushed to the Senate house, where they immediately passed a motion

condemning his memory to oblivion. Under the rulers of the Nervan-Antonian

dynasty, senatorial authors published histories that elaborated on the

view of Domitian as a tyrant.

Nevertheless, the evidence suggests that Domitian did make concessions

toward senatorial opinion. Whereas his father and brother had concentrated

consular power largely in the hands of the Flavian family, Domitian admitted

a surprisingly large number of provincials and potential opponents to the

consulship, allowing them to head the official calendar by opening the

year as an ordinary consul. Whether this was a genuine attempt to

reconcile with hostile factions in the Senate cannot be ascertained. By

offering the consulship to potential opponents, Domitian may have wanted

to compromise these senators in the eyes of their supporters. When

their conduct proved unsatisfactory, they were almost invariably brought

to trial and exiled or executed, and their property was confiscated.

Both Tacitus and Suetonius speak of escalating persecutions toward the

end of Domitian's reign, identifying a point of sharp increase around 93,

or sometime after the failed revolt of Saturninus in 89. At least

twenty senatorial opponents were executed, including Domitia Longina's

former husband Lucius Aelius Lamia and three of Domitian's own family members,

Titus Flavius Sabinus, Titus Flavius Clemens and Marcus Arrecinus Clemens.

Some of these men were executed as early as 83 or 85 however, lending little

credit to Tacitus' notion of a "reign of terror" late in Domitian's reign.

According to Suetonius, some were convicted for corruption or treason,

others on trivial charges, which Domitian justified through his suspicion:

"He used to say that the lot of Emperors was most unfortunate, since when

they discovered a conspiracy, no one believed them unless they had been

murdered."

Jones compares the executions of Domitian to those under Emperor Claudius

(41–55), noting that Claudius executed around 35 senators and 300 equestrians,

and yet was still deified by the Senate and regarded as one of the good

Emperors of history. Domitian was apparently unable to gain support

among the aristocracy, despite attempts to appease hostile factions with

consular appointments. His autocratic style of government accentuated

the Senate's loss of power, while his policy of treating patricians and

even family members as equals to all Romans earned him their contempt.

Death and succession

Assassination (96):

According to Suetonius, Domitian worshipped Minerva as his protector goddess

with superstitious veneration. In a dream, she is said to have abandoned

the emperor prior to the assassination.

Domitian was assassinated on 18 September 96, in a palace conspiracy organized

by court officials. A highly detailed account of the plot and the

assassination is provided by Suetonius, who alleges that Domitian's chamberlain

Parthenius was the chief instigator behind the conspiracy, citing the recent

execution of Domitian's secretary Epaphroditus as the primary motive.

The murder itself was carried out by a freedman of Parthenius named Maximus,

and a steward of Domitian's niece Flavia Domitilla, named Stephanus.

The precise involvement of the Praetorian Guard is less clear. At

the time the Guard was commanded by Domitian's relative Titus Flavius Norbanus,

former governor of the province of Raetia, and Titus Petronius Secundus

and the latter was almost certainly aware of the plot. Cassius Dio,

writing nearly a hundred years after the assassination, includes Domitia

Longina among the conspirators, but in light of her attested devotion to

Domitian—even years after her husband had died—her involvement in the plot

seems highly unlikely.

Dio further suggests that the assassination was improvised, while Suetonius

implies a well-organized conspiracy. For some days before the attack

took place, Stephanus feigned an injury so as to be able to conceal a dagger

beneath his bandages. On the day of the assassination the doors to

the servants' quarters were locked while Domitian's personal weapon of

last resort, a sword he concealed beneath his pillow, had been removed

in advance.

In accordance with an astrological prediction the Emperor believed that

he would die around noon, and was therefore restless during this time of

the day. On his last day, Domitian was feeling disturbed and asked

a servant several times what time it was. The boy, included in the

plot, lied, saying that it was much later than noon. More at ease,

the Emperor went to his desk to sign some decrees, where, according to

Suetonius, he was suddenly approached by Stephanus: "Then pretending

to betray a conspiracy and for that reason being given an audience, [Stephanus]

stabbed the emperor in the groin as he was reading a paper which the assassin

handed him, and stood in a state of amazement. As the wounded prince attempted

to resist, he was slain with seven wounds by Clodianus, a subaltern, Maximus,

a freedman of Parthenius, Satur, decurion of the chamberlains, and a gladiator

from the imperial school."

Domitian and Stephanus wrestled on the ground for some time, until the

Emperor was finally overpowered and fatally stabbed by the conspirators;

Stephanus was stabbed by Domitian during the struggle and died shortly

afterward. Around noon Domitian, just one month short of his 45th

birthday, was dead. His body was carried away on a common bier, and

unceremoniously cremated by his nurse Phyllis, who later mingled the ashes

with those of his niece Julia, at the Flavian temple.

According to Suetonius, a number of omens had foretold Domitian's death.

Several days prior to the assassination, Minerva had appeared to him in

a dream, announcing she had been disarmed by Jupiter and would no longer

be able to protect him.

Succession and aftermath:

The Fasti Ostienses, the Ostian Calendar, records that the same day the

Senate proclaimed Marcus Cocceius Nerva emperor. Despite his political

experience, this was a remarkable choice. Nerva was old and childless,

and had spent much of his career out of the public light, prompting both

ancient and modern authors to speculate on his involvement in Domitian's

assassination.

According to Cassius Dio, the conspirators approached Nerva as a potential

successor prior to the assassination, suggesting that he was at least aware

of the plot. He does not appear in Suetonius' version of the events,

but this may be understandable, since his works were published under Nerva's

direct descendants Trajan and Hadrian. To suggest the dynasty owed

its accession to murder would have been less than sensitive.

On the other hand, Nerva lacked widespread support in the Empire, and as

a known Flavian loyalist, his track record would not have recommended him

to the conspirators. The precise facts have been obscured by history,

but modern historians believe Nerva was proclaimed Emperor solely on the

initiative of the Senate, within hours after the news of the assassination

broke. The decision may have been hasty so as to avoid civil war,

but neither appears to have been involved in the conspiracy.

The Senate nonetheless rejoiced at the death of Domitian, and immediately

following Nerva's accession as Emperor, passed damnatio memoriae on his

memory: his coins and statues were melted, his arches were torn down and

his name was erased from all public records. Domitian and, over a

century later, Publius Septimius Geta were the only emperors known to have

officially received a damnatio memoriae, though others may have received

de facto ones. In many instances, existing portraits of Domitian,

such as those found on the Cancelleria Reliefs, were simply recarved to

fit the likeness of Nerva, which allowed quick production of new images

and recycling of previous material. Yet the order of the Senate was

only partially executed in Rome, and wholly disregarded in most of the

provinces outside Italy.

According to Suetonius, the people of Rome met the news of Domitian's death

with indifference, but the army was much grieved, calling for his deification

immediately after the assassination, and in several provinces rioting.

As a compensation measure, the Praetorian Guard demanded the execution

of Domitian's assassins, which Nerva refused. Instead he merely dismissed

Titus Petronius Secundus, and replaced him with a former commander, Casperius

Aelianus.

Dissatisfaction with this state of affairs continued to loom over Nerva's

reign, and ultimately erupted into a crisis in October 97, when members

of the Praetorian Guard, led by Casperius Aelianus, laid siege to the Imperial

Palace and took Nerva hostage. He was forced to submit to their demands,

agreeing to hand over those responsible for Domitian's death and even giving

a speech thanking the rebellious Praetorians. Titus Petronius Secundus

and Parthenius were sought out and killed. Nerva was unharmed in this assault,

but his authority was damaged beyond repair. Shortly thereafter he

announced the adoption of Trajan as his successor, and with this decision

all but abdicated.

Legacy

Ancient sources:

The classic view of Domitian is usually negative, since most of the antique

sources were related to the Senatorial or aristocratic class, with which

Domitian had notoriously difficult relations. Furthermore, contemporary

historians such as Pliny the Younger, Tacitus and Suetonius all wrote down

the information on his reign after it had ended, and his memory had been

condemned to oblivion. The work of Domitian's court poets Martial

and Statius constitutes virtually the only literary evidence concurrent

with his reign. Perhaps as unsurprising as the attitude of post-Domitianic

historians, the poems of Martial and Statius are highly adulatory, praising

Domitian's achievements as equalling those of the gods.

The most extensive account of the life of Domitian to survive was written

by the historian Suetonius, who was born during the reign of Vespasian,

and published his works under Emperor Hadrian (117–138). His De Vita

Caesarum is the source of much of what is known of Domitian. Although

his text is predominantly negative, it neither exclusively condemns nor

praises Domitian, and asserts that his rule started well, but gradually

declined into terror. The biography is problematic however, in that

it appears to contradict itself with regards to Domitian's rule and personality,

at the same time presenting him as a conscientious, moderate man, and as

a decadent libertine.

According to Suetonius, Domitian wholly feigned his interest in arts and

literature, and never bothered to acquaint himself with classic authors.

Other passages, alluding to Domitian's love of epigrammatic expression,

suggest that he was in fact familiar with classic writers, while he also

patronized poets and architects, founded artistic Olympics, and personally

restored the library of Rome at great expense after it had burned down.

De Vita Caesarum is also the source of several outrageous stories regarding

Domitian's marriage life. According to Suetonius, Domitia Longina was exiled

in 83 because of an affair with a famous actor named Paris. When

Domitian found out, he allegedly murdered Paris in the street and promptly

divorced his wife, with Suetonius further adding that once Domitia was

exiled, Domitian took Julia as his mistress, who later died during a failed

abortion.

Modern historians consider this highly implausible however, noting that

malicious rumours such as those concerning Domitia's alleged infidelity

were eagerly repeated by post-Domitianic authors, and used to highlight

the hypocrisy of a ruler publicly preaching a return to Augustan morals,

while privately indulging in excesses and presiding over a corrupt court.

Nevertheless, the account of Suetonius has dominated imperial historiography

for centuries.

Although Tacitus is usually considered to be the most reliable author of

this era, his views on Domitian are complicated by the fact that his father-in-law,

Gnaeus Julius Agricola, may have been a personal enemy of the Emperor.

In his biographical work Agricola, Tacitus maintains that Agricola was

forced into retirement because his triumph over the Caledonians highlighted

Domitian's own inadequacy as a military commander. Several modern

authors such as Dorey have argued the opposite: that Agricola was in fact

a close friend of Domitian, and that Tacitus merely sought to distance

his family from the fallen dynasty once Nerva was in power.

Tacitus' major historical works, including The Histories and Agricola's

biography, were all written and published under Domitian's successors Nerva

(96–98) and Trajan (98–117). Unfortunately, the part of Tacitus'

Histories dealing with the reign of the Flavian dynasty is almost entirely

lost. His views on Domitian survive through brief comments in its

first five books, and the short but highly negative characterization in

Agricola in which he severely criticizes Domitian's military endeavours.

Nevertheless, Tacitus admits his debt to the Flavians with regard to his

own public career.

Other influential 2nd century authors include Juvenal and Pliny the Younger,

the latter of whom was a friend of Tacitus and in 100 delivered his famous

Panegyricus Traiani before Trajan and the Roman Senate, exalting the new

era of restored freedom while condemning Domitian as a tyrant. Juvenal

savagely satirized the Domitianic court in his Satires, depicting the Emperor

and his entourage as corrupt, violent and unjust. As a consequence,

the anti-Domitianic tradition was already well established by the end of

the 2nd century, and by the 3rd century, even expanded upon by early Church

historians, who identified Domitian as an early persecutor of Christians,

such as in the Acts of John.

Modern revisionism:

Hostile views of Domitian were propagated until well into the early 20th

century, before archeological and numismatic advances brought renewed attention

to his reign, and necessitated a revision of the literary tradition established

by Tacitus and Pliny. In 1930, Ronald Syme argued a complete reassessment

of Domitian's financial policy, which had until then been largely viewed

as a disaster, opening his paper with the following introduction:

"The work of the spade and the use of common sense have done much to mitigate

the influence of Tacitus and Pliny and redeem the memory of Domitian from

infamy or oblivion. But much remains to be done."

Over the course of the 20th century, Domitian's military, administrative

and economic policies were re-evaluated. New book length studies

were not published until the 1990s however, nearly a hundred years after

Stéphane Gsell's Essai sur le règne de l'empereur Domitien

(1894). The most important of these was The Emperor Domitian, by

Brian W. Jones. In his monograph, Jones concludes that Domitian was

a ruthless, but efficient autocrat. For the majority of his reign,

there was no widespread dissatisfaction with the emperor or his rule.

His harshness was felt by only a small, but highly vocal minority, who

later exaggerated his despotism in favour of the well-regarded Nervan-Antonian

dynasty that followed.

Domitian's foreign policy was realistic, rejecting expansionist warfare

and negotiating peace at a time when Roman military tradition dictated

aggressive conquest. His economic program, which was rigorously efficient,

maintained the Roman currency at a standard it would never again achieve.

Persecution of religious minorities, such as Jews and Christians, was non-existent.

Domitian's government nonetheless exhibited totalitarian characteristics.

As Emperor, he saw himself as the new Augustus, an enlightened despot destined

to guide the Roman Empire into a new era of Flavian renaissance.

Religious, military and cultural propaganda fostered a cult of personality.

He deified three of his family members and erected massive structures to

commemorate the Flavian achievements. Elaborate triumphs were celebrated

in order to boost his image as a warrior-emperor, but many of these were

either unearned or premature. By nominating himself perpetual censor,

he sought to control public and private morals.

He became personally involved in all branches of the government and successfully

prosecuted corruption among public officials. The dark side of his

censorial power involved a restriction in freedom of speech, and an increasingly

oppressive attitude toward the Roman Senate. He punished libel with

exile or death and, due to his suspicious nature, increasingly accepted

information from informers to bring false charges of treason if necessary.

Although contemporary historians vilified Domitian after his death, his

administration provided the foundation for the Principate of the peaceful

2nd century. His successors Nerva and Trajan were less restrictive,

but in reality their policies differed little from Domitian's. Much

more than a "gloomy coda to the...1st century" the Roman Empire prospered

between 81 and 96, in a reign that Theodor Mommsen described as the sombre

but intelligent despotism of Domitian.

Information was taken from Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

at this URL:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Domitian

|